Last week my Medieval Monday post talked about cooking methods without the benefits of a modern kitchen. Today is part two of that post.

I previously mentioned a type of earth oven which was really just a pit in the ground, primarily used for things like meat, which could be wrapped up and placed directly on and under hot coals or rocks. But people of the Anglo-Saxon and Medieval period also had their version of a hot air oven, which didn’t change much even up until the 18th Century. They could be large enough for a person to climb inside, or just big enough to hold a loaf of bread, depending on the means and the need of the person using it. Obviously manor and castle kitchens and bake houses would have had to be very large to accommodate the feeding of hundreds of people when necessary. Many peasant households didn’t have an oven at all, relying on a communal bake house, or buying bread from the local baker. While we’re accustomed to having our ovens right inside our homes, ovens of this era were typically built apart from other structures because they were such a fire hazard.

Medieval ovens came in different shapes and sizes, and building materials might vary depending on what was readily available. Common materials were clay, tiles, stone, or combinations of the three. Some ovens were built so that flues carried hot air around it on the outsides. But more typically an oven was heated by lighting brushwood on the inside. The brushwood was kept burning until the structure was hot enough to maintain a proper baking temperature. This might take many hours—the larger the oven, the longer it would take to heat it. Once it was hot enough, the remaining coal and ashes were scraped out and the food inserted. The opening to the oven would then be covered and the food left inside for the appropriate cooking time. Such ovens could be used for any kind of baking, including meats, breads, cakes, and pies.

I’ve included two interesting videos this week, since watching (or participating in) a hands on experience always adds an additional layer of understanding. The first shows how one type of medieval oven was built, and the other shows how it was heated and used for baking. The title is 18th Century Cooking, but as is pointed out in the video, this method hadn’t really changed since long before the Middle Ages, so the information is still applicable. They are both very well done. Enjoy!

Building an Oven:

Baking Bread in the Oven: (Listen for additional details of what might be baked in these ovens, and the special order in which they were baked, to make the best use of the oven as it gradually reduced in temperature.)

.

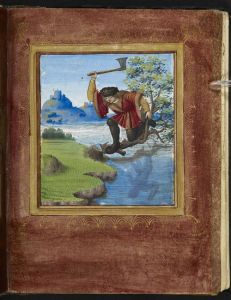

Managing your fuel supply was a key element. Cutting and gathering wood was a summer task, though it might not be split until winter. How much wood was needed throughout the year for cooking and heat depended on how large your household was. A wealthy household or lord would have access to wooded areas that peasants were not allowed to touch.

Managing your fuel supply was a key element. Cutting and gathering wood was a summer task, though it might not be split until winter. How much wood was needed throughout the year for cooking and heat depended on how large your household was. A wealthy household or lord would have access to wooded areas that peasants were not allowed to touch. Once you had a source of heat, the easiest cooking method was of course, direct heat; roasting meat over an open flame, or placing food in a container over, on, under or next to the fire. Different types of wood might be used depending on what was being cooked.

Once you had a source of heat, the easiest cooking method was of course, direct heat; roasting meat over an open flame, or placing food in a container over, on, under or next to the fire. Different types of wood might be used depending on what was being cooked.