There is no doubt now, that fall is here. The weather is getting cooler, and the labors of summer have produced an abundant harvest. It is a time of plenty in the medieval world, albeit a cautious one. The harsh winter months are only just ahead, and what has been so carefully grown and collected must now also be preserved to ensure the survival of the community.

The last of the winter grains are being sown in the fallow fields, and grapes are still being harvested for the production of wine, and a common medieval condiment called verjuice; a clear, sour juice made from unripe grapes, apples, berries, or other fruit. It was used mainly for cooking and adding flavor to foods.

The last of the winter grains are being sown in the fallow fields, and grapes are still being harvested for the production of wine, and a common medieval condiment called verjuice; a clear, sour juice made from unripe grapes, apples, berries, or other fruit. It was used mainly for cooking and adding flavor to foods.

October was a time to gather whatever wild nuts and fruits might still be found and preserve them for winter. It was also a time to make decisions about livestock, because storing enough food to feed them all through winter was costly and impractical. Cattle were the first to be fattened by permitting them to wander the fields and eat from leftover stubble. Sheep were the last, because they cropped everything so close to the ground they didn’t leave much behind.

Pigs, a common sight in every village, were allowed to roam free and forage wherever they could year round. They were only semi-domesticated animals; lean and with coarse hair. They typically lived on what they could find, including scraps, and when well-fed in fall, quickly put on weight. It was said that “a pig that needed to be fed on grain was not worth keeping.” Since acorns were a favorite food of pigs, woods full of oak trees were especially prized for fattening them. Beechnuts, hazel nuts, and hawes were also favored by swineherds, who watched for the first signs that those trees were ready to drop. Poultry would be fattened as well, particularly geese, then slaughtered before they could lose their fat.

Pigs, a common sight in every village, were allowed to roam free and forage wherever they could year round. They were only semi-domesticated animals; lean and with coarse hair. They typically lived on what they could find, including scraps, and when well-fed in fall, quickly put on weight. It was said that “a pig that needed to be fed on grain was not worth keeping.” Since acorns were a favorite food of pigs, woods full of oak trees were especially prized for fattening them. Beechnuts, hazel nuts, and hawes were also favored by swineherds, who watched for the first signs that those trees were ready to drop. Poultry would be fattened as well, particularly geese, then slaughtered before they could lose their fat.

The 14th century husband-to-be who wrote the Medieval Home Companion had the following advice for his young bride regarding the month of October:

In October plant peas and beans a finger deep in the earth and a handbreadth from each other. Plant the biggest beans, for when they are new these prove themselves to be larger than the smaller ones can ever become. Plant only a few of them, and at each waning of the moon afterward, a few more so that if some of them freeze, the others will not. If you want to plant pierced peas, sow them in weather that is dry and pleasant, not rainy, for if rain water gets into the openings of the peas, they will crack and split in two and not germinate.

Up until All Saints’ Day you can always transplant cabbages. When they are so much eaten by caterpillars that there is nothing left of the leaves except the ribs, all will come back as sprouts if they are transplanted. Remove the lower leaves and replant the cabbages to the depth of the upper bud. Do not replant the stems that are completely defoliated; leave these in the ground, for they will send up sprouts. If you replant in summer and the weather is dry, you must pour water in the hole; this is not necessary in wet weather

If caterpillars eat the cabbages, spread cinders under the cabbages when it rains and the caterpillars will die. If you look under the leaves of the cabbages, you will find there a great collection of small white morsels in a heap. This is where the caterpillars are born, and therefore you should cut off the part with these eggs and throw it away. Leeks are sown in season, then transplanted in October and November.

There are more Tales from the Green Valley to enjoy! This episode includes roofing with timbers and thatch, gardening, harvesting pears, period footwear, fattening the pigs, spit roasting lamb, storing/checking fruit for winter. Want to learn more about daily medieval life? Check out the Medieval Monday Index.

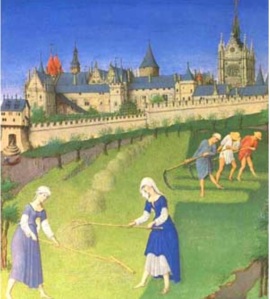

Medieval people had a heightened awareness of seasonal changes. The onset of autumn brought about a final burst of activity as they prepared themselves to endure an inevitable winter. The grain harvest that had begun in summer continued into fall, with threshing and winnowing of what had already been reaped from the fields. At the same time legumes, such as peas and beans, were gathered after they had dried on the plants. Never letting anything go to waste, the leftover leaves and stems could be used to feed the animals, or plowed under as fertilizer. Some fields would be plowed anew with seeds for rye and winter wheat.

Medieval people had a heightened awareness of seasonal changes. The onset of autumn brought about a final burst of activity as they prepared themselves to endure an inevitable winter. The grain harvest that had begun in summer continued into fall, with threshing and winnowing of what had already been reaped from the fields. At the same time legumes, such as peas and beans, were gathered after they had dried on the plants. Never letting anything go to waste, the leftover leaves and stems could be used to feed the animals, or plowed under as fertilizer. Some fields would be plowed anew with seeds for rye and winter wheat. New wine was the most common drink, which had very limited alcohol content. But stronger wines were also produced, and could be watered down if needed. There were many more variations in taste, smell, and color than people are accustomed to today. Wines might be red, gold, pink, green, white, or such a dark red that it had a black appearance. There was also a variety of flavor–some were pleasant and sweet (usually reserved for special occasions), where others might be more bitter, or even vinegary.

New wine was the most common drink, which had very limited alcohol content. But stronger wines were also produced, and could be watered down if needed. There were many more variations in taste, smell, and color than people are accustomed to today. Wines might be red, gold, pink, green, white, or such a dark red that it had a black appearance. There was also a variety of flavor–some were pleasant and sweet (usually reserved for special occasions), where others might be more bitter, or even vinegary. Sometimes the type of wine chosen was dependent on the season (and which bodily humors were at play), on age, or on the state of one’s health. Melancholy was thought to be the dominant humour in autumn, which was “cold and dry.” The Secretum Secretorum advocated specific foods, drink, and activities to combat the negative effects. “Hot moist foods like chicken, lamb and sweet grapes should be eaten and fine old wines drunk, to ward of melancholy…Overmuch exercise and lovemaking are not recommended…but the heat and moisture of warm baths are helpful in keeping melancholy under control.”

Sometimes the type of wine chosen was dependent on the season (and which bodily humors were at play), on age, or on the state of one’s health. Melancholy was thought to be the dominant humour in autumn, which was “cold and dry.” The Secretum Secretorum advocated specific foods, drink, and activities to combat the negative effects. “Hot moist foods like chicken, lamb and sweet grapes should be eaten and fine old wines drunk, to ward of melancholy…Overmuch exercise and lovemaking are not recommended…but the heat and moisture of warm baths are helpful in keeping melancholy under control.” Other labors of September included gathering honey and wax from beehives, which would then be moved to suitable locations for winter. Cows would be bred to ensure there would be young calves in the spring. Any cattle, or other livestock, that there were not enough resources to feed through the winter would be sold or butchered for meat. The meat would then be salted, smoked, or otherwise preserved in anticipation of the winter to come. At the end of September, on Michaelmas, lords and other debtors collected their rents and payments.

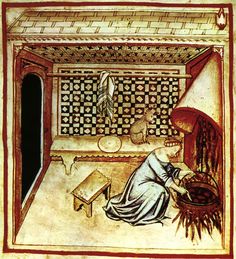

Other labors of September included gathering honey and wax from beehives, which would then be moved to suitable locations for winter. Cows would be bred to ensure there would be young calves in the spring. Any cattle, or other livestock, that there were not enough resources to feed through the winter would be sold or butchered for meat. The meat would then be salted, smoked, or otherwise preserved in anticipation of the winter to come. At the end of September, on Michaelmas, lords and other debtors collected their rents and payments. There is a persistent rumor that water was avoided due to widespread contamination of waterways by pollutants and bacteria. This is actually not the case. While plain water was certainly nothing exciting enough to sing songs about, it was regularly drunk by itself, or used to water down other drinks. Even though they had no concept of what bacteria were, medieval people were smart enough to distinguish fresh from polluted water, and carefully avoided the latter. Large cities in fact invested considerable wealth into reliable water systems that would bring in fresh water from springs or other sources. Waterways used for industry were avoided as drinking sources, as were stagnant or marshy waters. Rainwater was thought to be the healthiest water, and it was easy enough for anyone to collect. There were instances when medieval physicians might advise against water, such as when eating a meal. Wine was recommended instead, as water was thought to “chill the stomach.” Ironically, a 15th century source advises pregnant women to beware of cold water, which was thought to be harmful to the fetus, and drink wine instead.

There is a persistent rumor that water was avoided due to widespread contamination of waterways by pollutants and bacteria. This is actually not the case. While plain water was certainly nothing exciting enough to sing songs about, it was regularly drunk by itself, or used to water down other drinks. Even though they had no concept of what bacteria were, medieval people were smart enough to distinguish fresh from polluted water, and carefully avoided the latter. Large cities in fact invested considerable wealth into reliable water systems that would bring in fresh water from springs or other sources. Waterways used for industry were avoided as drinking sources, as were stagnant or marshy waters. Rainwater was thought to be the healthiest water, and it was easy enough for anyone to collect. There were instances when medieval physicians might advise against water, such as when eating a meal. Wine was recommended instead, as water was thought to “chill the stomach.” Ironically, a 15th century source advises pregnant women to beware of cold water, which was thought to be harmful to the fetus, and drink wine instead. In the northernmost regions of Europe where grapes did not grow, most of the alcohol consumed were beer or ale, both of which were much weaker than the modern day versions, and might be further watered down if desired. Ale was the most common, brewed with barley but not hops. “Small Ale” (or “Small Beer”) had extremely low alcohol content and was actually considered an important source of hydration and nutrition. It was a cloudy drink, consumed fresh, and would have been drunk on a daily basis by just about everyone, even youth. Ale with higher alcohol content would have been saved for recreational purposes due to the intoxicating effects. Beer was at first brewed with “gruit,” a mix of various herbs, then gradually with hops as brewers figured out the proper ratio to use. Hops was a better preservative, allowing beer to be stored for 6 months or longer, whereas beer brewed with gruit needed to be consumed more quickly. Wine was only drunk by those who could afford to import it.

In the northernmost regions of Europe where grapes did not grow, most of the alcohol consumed were beer or ale, both of which were much weaker than the modern day versions, and might be further watered down if desired. Ale was the most common, brewed with barley but not hops. “Small Ale” (or “Small Beer”) had extremely low alcohol content and was actually considered an important source of hydration and nutrition. It was a cloudy drink, consumed fresh, and would have been drunk on a daily basis by just about everyone, even youth. Ale with higher alcohol content would have been saved for recreational purposes due to the intoxicating effects. Beer was at first brewed with “gruit,” a mix of various herbs, then gradually with hops as brewers figured out the proper ratio to use. Hops was a better preservative, allowing beer to be stored for 6 months or longer, whereas beer brewed with gruit needed to be consumed more quickly. Wine was only drunk by those who could afford to import it. Like beers and ales, the quality of wine varied greatly, with that made of second and third pressings the lowest quality with the least alcohol content. These would have been the equivalent of “small ale”—a drink consumed daily by just about everyone, and even in large quantities, without concerns about intoxication. The poorest peasants might have to settle for watered down vinegar as their daily drink. Fine, expensive wines with much higher alcohol content would have been made from the first pressings of grapes. Such wine might also be mulled or spiced—also considered to be quite healthy. Red wine would be combined with sugar and spices such as nutmeg, ginger, cardamom, pepper, and cloves among others.

Like beers and ales, the quality of wine varied greatly, with that made of second and third pressings the lowest quality with the least alcohol content. These would have been the equivalent of “small ale”—a drink consumed daily by just about everyone, and even in large quantities, without concerns about intoxication. The poorest peasants might have to settle for watered down vinegar as their daily drink. Fine, expensive wines with much higher alcohol content would have been made from the first pressings of grapes. Such wine might also be mulled or spiced—also considered to be quite healthy. Red wine would be combined with sugar and spices such as nutmeg, ginger, cardamom, pepper, and cloves among others. Here I want to speak a bit about clothes. Concerning this, dear sister, if you will take my advice, you will be very careful and pay great attention to your resources and means, in accordance with the social status of your relations and mine, whom you will visit and be with every day. Take care that you are respectably dressed, without introducing new fashions, and without too much, or too little, ostentation. Before you leave your room or the house, first see that the collars of your shift, your petticoat, your frock, or your coat do not overlap, as is the case with some drunken, silly, or ignorant women, who, not considering their reputation or the propriety of their rank or that of their husbands, go about with gaping eyes, heads appallingly elevated, like a lion, their hair sticking out of their headdresses, and the collars of their shifts and dresses overlapping—walking mannishly and conducting themselves before people indecently and without shame…So take care, fair sister, that your hair, your cap, your kerchief, your hood, and the rest of your attire are neatly and simply arranged, so that no one who sees you can laugh at you or mock you. Instead, you should be to all the others an example of order, simplicity, and decorum.

Here I want to speak a bit about clothes. Concerning this, dear sister, if you will take my advice, you will be very careful and pay great attention to your resources and means, in accordance with the social status of your relations and mine, whom you will visit and be with every day. Take care that you are respectably dressed, without introducing new fashions, and without too much, or too little, ostentation. Before you leave your room or the house, first see that the collars of your shift, your petticoat, your frock, or your coat do not overlap, as is the case with some drunken, silly, or ignorant women, who, not considering their reputation or the propriety of their rank or that of their husbands, go about with gaping eyes, heads appallingly elevated, like a lion, their hair sticking out of their headdresses, and the collars of their shifts and dresses overlapping—walking mannishly and conducting themselves before people indecently and without shame…So take care, fair sister, that your hair, your cap, your kerchief, your hood, and the rest of your attire are neatly and simply arranged, so that no one who sees you can laugh at you or mock you. Instead, you should be to all the others an example of order, simplicity, and decorum. Know, dear sister, that after your husband, you must be mistress of the house—master, overseer, ruler, and chief administrator—and it is up to you to keep the maidservants subservient and obedient to you, and to teach, reprove, and correct them. And so, prohibit them from lessening their worth by engaging in life’s gluttony and excesses. Also prevent them from quarreling with each other and with your neighbors. Don’t let them speak ill of others, except to you and in secret, and only insofar as the offense affects your interests and to avoid harm to yourself. Forbid them to lie, to play unlawful games, to swear foully, and to speak words that suggest villainy or that are lewd or coarse, like some vulgar people who curse “the bloody bad fevers, the bloody bad work, the bloody bad day.”

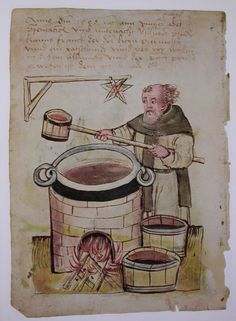

Know, dear sister, that after your husband, you must be mistress of the house—master, overseer, ruler, and chief administrator—and it is up to you to keep the maidservants subservient and obedient to you, and to teach, reprove, and correct them. And so, prohibit them from lessening their worth by engaging in life’s gluttony and excesses. Also prevent them from quarreling with each other and with your neighbors. Don’t let them speak ill of others, except to you and in secret, and only insofar as the offense affects your interests and to avoid harm to yourself. Forbid them to lie, to play unlawful games, to swear foully, and to speak words that suggest villainy or that are lewd or coarse, like some vulgar people who curse “the bloody bad fevers, the bloody bad work, the bloody bad day.” …stir it often, pressing your spoon against the bottom of the pot so that it won’t stick there. As soon as you notice that it is sticking, stop stirring it, take it off the fire immediately, and put it in another pot.

…stir it often, pressing your spoon against the bottom of the pot so that it won’t stick there. As soon as you notice that it is sticking, stop stirring it, take it off the fire immediately, and put it in another pot.